7 minute video (see below) on Chapter 23 – Slowing down time from the A Practical EmPath: Rewire Your Mind book by Scott Howard Swain. Direct YouTube link: https://youtu.be/pMH4xhYFosE

video created with the help of AI tools

Chapter Summary

This document synthesizes the core principles from Chapter 23, “Slowing down time,” of Scott Howard Swain’s A Practical EmPath. The chapter’s central argument is that in an age of speed and distraction, the deliberate practice of slowing down is essential for reducing stress, improving physical and psychological health, and experiencing life more fully. This “slowing down” is not a literal manipulation of time but a subjective expansion of one’s awareness and presence in the moment.

The text posits that practices such as mindful eating, meditation, and slow-movement exercises like Tai Chi are practical methods for cultivating this presence. These activities train the brain to be fully engaged in the “here and now,” thereby reducing the production of the stress hormone cortisol and fostering a state of calm. The benefits of these practices are shown to be deeply interconnected with the principles of Practical Empathy Practice (PEP), as they develop the non-reactive, consciously aware state of mind necessary for genuine empathy. Ultimately, the chapter concludes that various mindfulness exercises serve as different “doorways into the same room”—a state where one is actively living life with intention rather than passively rushing through it.

The Central Thesis: The Urgency of Slowing Down

The foundational premise of the chapter is that a hurried lifestyle is detrimental to well-being. Rushing through life is directly correlated with increased stress and the production of cortisol, “the stress hormone,” which in turn signals the body to store fat. The author reframes the concept of “winning the race” not as achieving things faster, but as reducing stress, avoiding unnecessary weight gain, and freeing up time to engage in personally meaningful activities. This philosophy is supported by insights from various thinkers who advocated for a more deliberate and essentialist approach to life.

|

Thinker |

Core Insight |

|

Pico Lyer |

“In an age of speed, nothing could be more invigorating than going slow… In an age of constant movement, nothing is more urgent than standing still.” |

|

Henry David Thoreau |

Advocated for living “deliberately” to face only life’s essential facts and learn its lessons. |

|

Arthur Schopenhauer |

Identified “hurry and bustle” as a prime cause of “fevered restlessness” and the pursuit of illusions mistaken for happiness. |

|

Marcus Aurelius |

Advised doing less but doing what is essential to achieve more time and tranquility, asking at every moment, “Is this necessary?” |

|

Lao Tzu |

Observed that “Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished,” promoting the concept of Wu Wei (effortless action) by aligning with the natural flow. |

|

Seneca |

Argued that the problem is not a short life, but that “we waste a lot of it.” |

Practical Empathy Practice (PEP) Framework

The chapter is framed within the context of Practical Empathy Practice (PEP), a system designed to improve connection and awareness. Key principles of PEP mentioned in the text include:

- Avoiding Evaluative Language: Instead of making judgments like calling someone a “short-cut-taking lying cheating cheater,” PEP encourages empathetic translations that inquire about the underlying feelings and needs, such as, “Did you skip ahead because you were bored and wanted more mental stimulation?”

- Individual Responsibility for Feelings: A core rule of PEP is that individuals do not “make” anyone feel anything; they may stimulate a feeling, but the other person chooses how to process it.

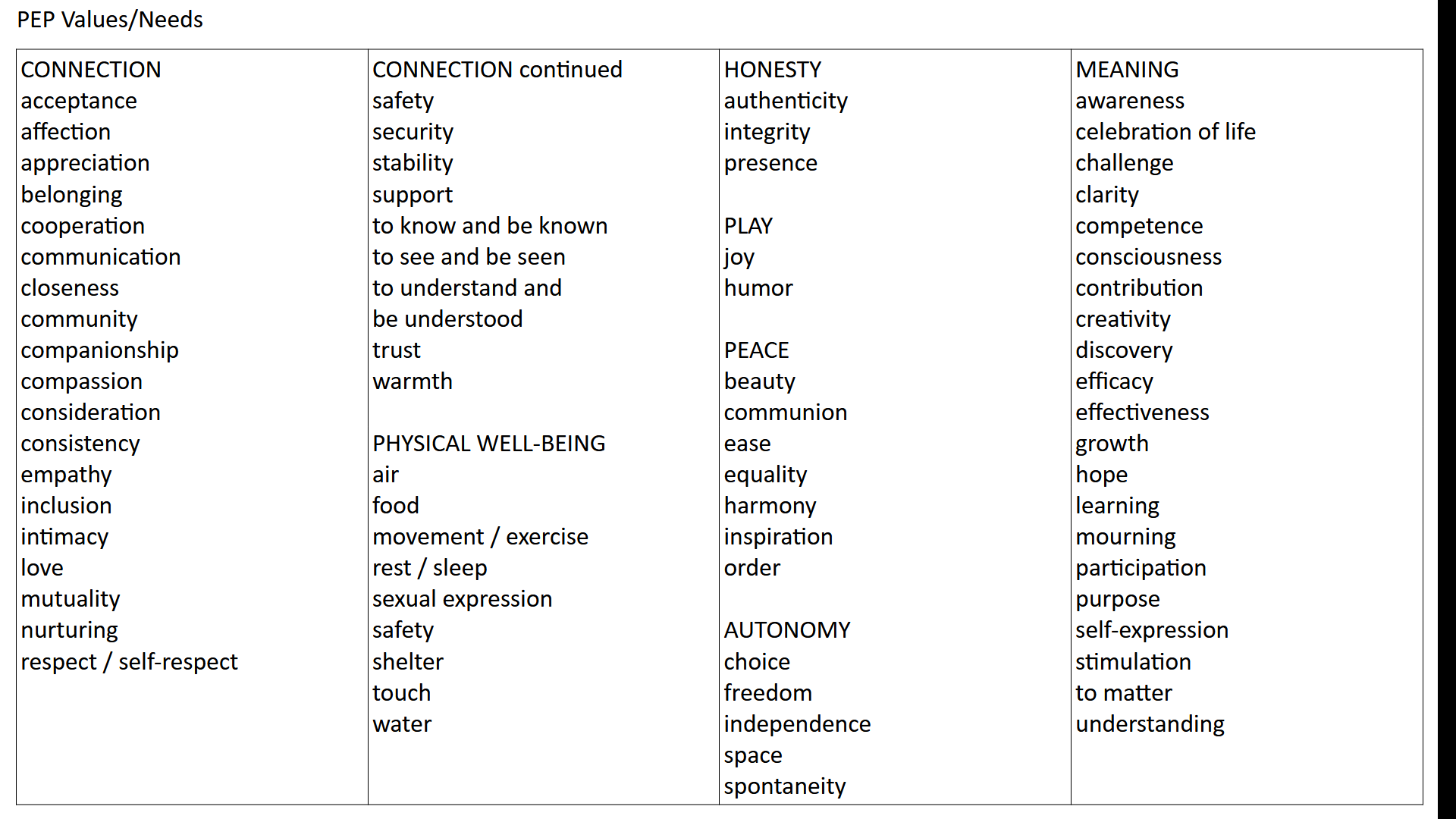

- Needs and Values: Within the PEP framework, the terms “needs” and “values” are treated as synonymous.

The practice of slowing down is presented as a fundamental support for PEP. The presence, reduced emotional charge, and ability to respond rather than react—all cultivated through mindfulness—are essential for effective empathetic engagement.

Core Practice I: Mindful Eating

Mindful eating is presented as a primary, accessible exercise for practicing presence. The state of mind before and during a meal is shown to affect food metabolism directly. A calm state can reduce cortisol levels, thereby mitigating the body’s signal to store fat.

The Process of Mindful Eating

The practice involves a series of deliberate steps designed to engage all senses and foster appreciation:

- Preparation: Take deep breaths to release bodily tension before beginning.

- Visual Observation: Notice the colors, shapes, and sizes of the food.

- Sensory Awareness: Acknowledge the physical urge to eat (e.g., salivation) without immediate action. Investigate the food’s aroma.

- Gratitude: Take a moment to appreciate the energy that went into the food’s production and preparation.

- Deliberate Action: Notice the feel of the utensil. After placing food in the mouth, it is important to put the utensil down.

- Savoring: Instead of chewing and swallowing quickly, feel the food’s temperature and shape. Notice how textures and flavors change during slow, complete chewing.

- Conscious Swallowing: Focus on the experience of swallowing itself.

- Pausing: Pause between bites, taking deep breaths and noticing any lingering flavors.

This process extends to appreciating the company of others and expressing gratitude for the meal.

Social Implications

The social impact of eating speed is explored through a list of pros and cons and a vivid narrative.

- Pros of Slow Eating: Enhances bonding, improves digestion, leads to eating less, increases joy, and decreases stress.

- Cons of Slow Eating: A snarky suggestion that it wastes time that could be spent on video games or “inventing quantum teleportation.”

- Illustrative Scenario: A date is described where one person’s appeal is rapidly diminished when they begin shoveling food into their mouth with “gooey liquidy squishy” sounds, leading their partner to feel nauseous and question their compatibility.

Core Practice II: Meditation as Focused Attention

The chapter defines meditation in an exceptionally broad and inclusive manner as “Anything you focus on to the exclusion of all else.” This definition moves beyond the misconception of meditation as a purely self-centered activity and reframes it as a practice of focused attention applicable to many areas of life.

The benefits of this broad form of meditation are presented as mapping directly onto the benefits of PEP:

- Self-knowing

- Acceptance

- Authenticity and courage

- Winning

- Power & Responsibility

- Contribution

- Being in the moment

- Patience

- Letting go

- Lie detection (Intuition)

Examples of activities that qualify as meditation under this definition include:

- Masturbation and sex

- Giving or receiving a massage

- Reading a book (noted as a direct way to build empathy by inhabiting another’s perspective)

- Cooking a meal

- Mindful eating

- Dancing

- Exercise

- Listening to music

- Being engrossed in a film

Core Practice III: Slow Movement (Tai Chi & Yoga)

Movement practices that emphasize slowness, breath coordination, and body awareness are highlighted as powerful tools for physical and mental well-being. Tai Chi, described as “moving meditation,” serves as the primary example.

Documented Benefits

- Neural Training: The deliberate pace of Tai Chi allows the nervous system time to optimize balance between muscle groups and integrate joint positions, improving motor efficiency and cognitive function.

- Physical Health: It improves balance and coordination, reducing the risk of falls in older adults. A 2018 study is cited, which found Tai Chi provided more pain relief than other exercises for individuals with fibromyalgia.

- Mental Health: The same study showed Tai Chi improved cognition in seniors with mild cognitive impairment. The practice’s rhythmic breathing reduces blood pressure and promotes relaxation.

- Mind-Body Connection: The required mindful attention strengthens body awareness.

The “Slowing Down Time” Hypothesis

The author, a long-time Shaolin Kung Fu practitioner, proposes a hypothesis based on personal experience. Consistent practice of moving slowly from a state of stillness can fine-tune perception to the point where one becomes highly sensitive to the micro-movements that precede a larger action.

- Neurological Reinforcement: Executing a complex movement (like a punch) slowly sends more signals between the body and brain, reinforcing neurological pathways and ingraining the motion into “muscle memory.”

- Subconscious Perception: This heightened sensitivity allows for the subconscious processing of an opponent’s initial, tiny movements. The response (a dodge or block) is also subconscious and feels incredibly fast or even precognitive, as if the opponent is moving in slow motion. This is presented as a tangible example of how one can “slow down time.”

The Unifying Principle: Interconnectivity of Practices

A key takeaway is that all these practices are mutually reinforcing. The skills developed in one area transfer to others, creating a positive feedback loop of increased presence and awareness.

- Practicing slow eating enhances one’s ability to be present, which in turn improves the ease of practicing Tai Chi.

- Practicing still meditation enhances one’s ease and joy during sex.

The chapter concludes by tying everything back to PEP:

- PEP requires presence.

- Presence requires slowing down.

- Slowing down requires practice.

Whether the practice is mindful eating, meditation, or Tai Chi, the goal is the same: to train the brain to inhabit the present moment. Meditation enhances PEP by making one more present and less reactive; PEP enhances meditation by providing tools to notice what is happening internally and externally. These practices are all doorways into a life that is actively and deliberately lived.

Prescribed Exercises for Cultivating Presence

The chapter concludes by offering six practical exercises to develop the skills discussed.

|

Exercise |

Description |

|

1. Mindful Observation |

Perform a routine daily task (e.g., brushing teeth) with total focus, observing every sound, sensation, and thought to see how awareness changes the experience. |

|

2. Empathy Reading |

While reading a novel or biography, consciously inhabit the characters’ perspectives. Afterward, write down their likely feelings, wants, and values. |

|

3. Focused Breathing |

For 5-10 minutes, sit quietly with eyes closed and focus solely on the physical sensations of breathing, gently returning focus whenever the mind wanders. |

|

4. Empathetic Listening to Music |

Listen to a piece of music with full attention, trying to understand the emotions, values, or desires the composer or musician might be expressing. |

|

5. Sensory Eating Practice |

During a meal, eat slowly and focus on the taste, texture, and aroma of each bite while considering the effort that brought the food to the table. |

|

6. Alternative Perspective |

Spend 10-15 minutes in a familiar space but from a new physical perspective (e.g., sitting on the floor in a corner) to notice new details and reflect on the role of perspective. |

The full values / needs list:

Recent Comments