video created with the help of AI tools

Summary

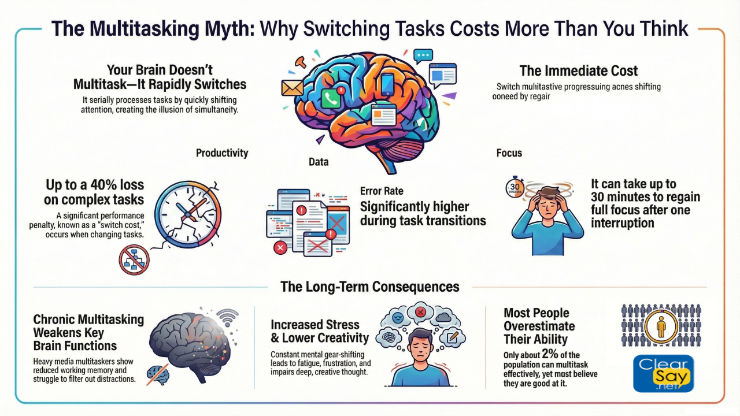

Research indicates that true multitasking is a myth because the human brain is architecturally limited to serial processing. What individuals perceive as doing multiple things at once is actually rapid task-switching, a taxing mental shift that leads to a 40% drop in productivity and increased error rates. While people can pair an automatic habit like walking with a mental task, attempting to juggle two complex activities creates a cognitive bottleneck in the prefrontal cortex. Chronic reliance on this behavior can lead to long-term memory issues, higher stress levels, and a significant decline in sustained attention. Ultimately, although specialized training can improve switching speed, it cannot bypass the brain’s fundamental inability to process competing demanding tasks simultaneously.

Detail

Task-Switching Costs and Cognitive Performance

Executive Summary

Research in cognitive science and neurobiology confirms that human “multitasking” is a misnomer. Rather than processing information in parallel, the human brain engages in rapid “task-switching,” a serial process that imposes significant cognitive and economic costs. This briefing outlines the architectural limitations of the brain, quantifies the performance penalties associated with switching, and examines the long-term cognitive and psychological effects of chronic multitasking.

Critical takeaways

* Productivity Erosion: Task-switching can cause a 40% loss in productive time and a temporary drop of approximately 10 IQ points.

* Architectural Bottleneck: The brain is a serial processor for cognitively demanding tasks, governed by specific executive control networks that cannot operate simultaneously.

* The “Switch Cost”: Every transition between tasks requires a “reconfiguration” period, leading to increased error rates and significant recovery times—up to 30 minutes to regain full focus after a brief interruption.

* Chronic Impact: Heavy media multitaskers exhibit reduced working memory, poorer attention filtering, and diminished memory consolidation compared to those who focus on single tasks.

The Cognitive Reality: Serial Processing vs. Parallel Execution

The human brain is architecturally incapable of performing multiple cognitively demanding tasks at once. What is perceived as multitasking is actually the brain rapidly alternating attention between tasks. This serial processing is managed by three primary executive control networks:

1. Frontoparietal Control Network: Sets task goals and priorities.

2. Dorsal Attention Network: Focuses attention on relevant, goal-oriented information.

3. Ventral Attention Network: Reorients attention to unexpected or external stimuli.

Neurological Coordination

The coordination of these networks occurs in specific regions of the brain. The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC) is responsible for configuring priorities and updating task sets during a switch. The Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (dlPFC) manages the interference caused by recently active competing tasks. This hierarchical engagement consumes metabolic resources and time, creating a “bottleneck” in the prefrontal cortex.

Quantifying the “Switch Cost”

The performance penalty incurred during the transition from one task to another is known as the “switch cost.” Even when switches are planned or predictable, the brain must suppress the rules of the previous task and activate the rules of the new one.

Performance Metrics and Findings

Productivity Loss Up to 40% loss for complex tasks due to context-switching overhead.

IQ Impact Multitasking can result in a temporary drop of 10 IQ points.

Error Rates Significantly higher during task-switching; complexity increases this cost.

Recovery Time An interruption every 3 minutes can require up to 30 minutes to regain deep focus.

Task Familiarity Switching to unfamiliar tasks results in slower transitions than familiar ones.

Exceptions: Automaticity and Hybrid Tasks

Humans can successfully execute multiple tasks simultaneously only when the tasks do not compete for the same cognitive resources.

* Automatic Tasks: Tasks that rely on subcortical and cerebellar processing (e.g., walking or chewing gum) require minimal cortical resources and do not interfere with high-level cognitive functions.

* Resource Competition: Interference becomes severe when tasks overlap in domain. For example, writing an email while talking on the phone is nearly impossible because both tasks compete for language processing resources within the prefrontal cortex.

* Passive Pairing: Listening to an audiobook while commuting is viable because one task is passive/habitual while the other is active.

Chronic Multitasking and Long-Term Cognitive Effects

Individuals who frequently engage in heavy media multitasking (HMM) show stable cognitive differences compared to low media multitaskers (LMM).

* Reduced Working Memory: HMMs show significantly lower working memory capacity.

* Attentional Deficits: HMMs struggle to filter out irrelevant information and maintain a broader attentional scope even when instructed to focus.

* Sustained Attention: Performance is lower on tasks requiring long-term focus, particularly when the cognitive demand of the task is low.

* Memory Consolidation: Constant switching impairs the brain’s ability to move information into long-term memory, reducing overall retention and recall.

Training, Plasticity, and Aging

While the brain exhibits plasticity, training does not change the fundamental serial nature of human cognition.

* Efficiency vs. Parallelism: Training can improve the speed of task-switching and reduce performance degradation, but it does not enable true parallel processing. The brain simply becomes more efficient at rapid serialization.

* Neuro-stimulation: Tools like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with training have shown potential in facilitating faster task-set updating.

* The Aging Factor: Multitasking becomes increasingly difficult with age. Older adults specifically struggle with “disengaging” from an interruption to re-establish focus on the primary task.

Neurobiological and Psychological Implications

Biological Signatures

Neuroimaging reveals that task-switching activates extensive neural machinery:

* Alpha Oscillations: Activation at 8–12 Hz in the frontoparietal cortex reflects the updating of task sets.

* Hemispheric Dominance: Task-switching processing is concentrated in the left frontoparietal region, while perceptual decision-making typically activates the right.

Psychological Consequences

The habit of constant task-switching leads to several negative health and wellness outcomes:

* Stress and Fatigue: Frequent switching correlates with increased frustration, job dissatisfaction, and “perpetual partial attention,” which leads to chronic mental fatigue.

* Creativity Suppression: Multitasking undermines the sustained attention required for deep insight and creative problem-solving.

* The Perception Gap: Approximately 98% of people are unable to multitask effectively, yet the vast majority believe they are above average in this skill. This misalignment encourages counterproductive behaviors.

Conclusion

The evidence from cognitive psychology and neuroscience suggests that maximizing productivity requires “sequential focus” rather than simultaneous effort. Defending blocks of focused work time is an economic and cognitive necessity, as the 40% productivity penalty associated with multitasking represents a substantial drain on intellectual and professional output. When multiple tasks must be handled, they should be paired strategically (one automatic, one demanding) to minimize resource competition.

Recent Comments